North Carolina Motorsports and Automotive Research Center

Attracting students from throughout the country and the world, performing research for top racing teams and automotive companies, and placing graduates on almost every NASCAR team, the Lee College of Engineering Motorsports Engineering program was one of the most exciting and successful programs at UNC Charlotte.

Early

Early

The origin of the program goes back to the mid-1990s, when Mechanical Engineering faculty members were asking out-of-state students what brought them to UNC Charlotte. The answer was almost always the same – “I want to get into racing.” One of the students giving this answer was Ryan Zeck, who had moved to UNC Charlotte from California to earn his mechanical engineering degree and to get his foot in to door in the Charlotte racing community. The first recipient of UNC Charlotte’s Kulwicki Scholarship, Zeck circulated a petition among fellow students that asked Mechanical Engineering to add a course in vehicle dynamics and more technical electives in motorsports-related topics. More than 75 students signed the petition.

“I met a lot of students who were from out of state and I was shocked that they had come so far to go to school,” said Bob Johnson, who was chair of Mechanical Engineering at the time. “When I asked them why they were here, they all said same thing, ‘I want to get into racing as an engineer or a crew chief.’ We weren’t really doing anything for these kids at the time and I started debating the options, figuring out what we could do. I sat down with Jerre Hill, who was the other key person interested in this, and we crafted a concentration area.”

Hill had always been a car person himself and was enthusiastic about starting an automotive and motorsports program. “It all happened because of Bob Johnson’s courage and vision,” Hill said. “We kept getting students who worked for race teams, and finally it occurred to us that we should start a program for these guys. I was kind of in right place at right time. I did realize ‘Hey this is a really good thing,’ and kind of by default I was the guy who was running it.”

Mechanical Engineering began offering more courses related to automotive and motorsports engineering, and at the same time it began working to get approval for an official concentration in that would be part of the Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering degree program. UNC Charlotte approved the concentration in Automotive and Motorsports Engineering in 1998.

Academics

To be part of the motorsports concentration, students applied for admission after successful completion of their freshman year. As sophomores, students accepted into the program enrolled in Motorsports Clinic I, where an increased emphasis was placed on applied automotive engineering education. During their junior and senior years, motorsports engineering students began a heavier concentration in automotive studies. All technical electives were taken from a list of motorsports engineering courses.

Many of the students coming into the program already had impressive backgrounds in racing, having been involved with family and local race teams. Sharing ideas with each other and with their professors, the students created a communal learning environment in the motorsports concentration. “We were all a bunch of gear heads,” Hill said, “and it worked.”

A key learning component of the program was the hands-on projects that were the foundation of the Lee College of Engineering’s education philosophy. Motorsports students worked on numerous class projects, as well as teams including Formula SAE, Mini Baja, ICARA, Human Powered Vehicle and the drag car. As part of the teams, students worked in the laboratory to design, build and test race cars and other vehicles. They learned the skills of real race teams such as project management, fabrication, race strategy, marketing and presentations, as well as engineering.

Some of the concentration courses included:

Some of the concentration courses included:

- Automotive Power Plants I and II

- Vehicle Aerodynamics

- Road Vehicle Dynamics

- Suspension Dynamics and Kinematics

- Motorsports Instrumentation

- Tire Dynamics

- Motorsports Engineering Clinics I, II and III

- Motorsports Administration

- Aerodynamics

- Computational Mechanics

- Drivetrain and Power Plants

- Instrumentation

Kulwicki Scholarship

Kulwicki Scholarship

In 1994, UNC Charlotte’s connection with the legacy of Alan Kulwicki began when R.J. Reynolds and racing fans helped establish the Alan Kulwicki Memorial Scholarship. Presented annually to an outstanding high school senior who had an affiliation with racing and was planning to major in mechanical engineering at UNC Charlotte, the four-year scholarship honored the memory of Kulwicki, who had been killed in a plane crash in 1993.

An engineering himself, Kulwicki was a trailblazer in the modern era of NASCAR racing as the first college graduate to win the NASCAR season championship and the first person to both own and drive for his own team. Kulwicki was a strong supporter of engineering and science education.

As the major sponsor of the NASCAR Winston Cup Series when the Kulwicki Scholarship was first established, R.J. Reynolds made sure the announcement of scholarship winners was done in proper racing style. Some of the first winners were introduced to crowds prior to the running of the Coca Cola 600 in Charlotte, complete with several speeches from Charlotte Motor Speedway, RJR and UNC Charlotte representatives, and photos with Miss Winston. As the first Kulwicki Scholarship winner, Zeck got to ride into the track in a convertible with the NASCAR drivers prior to the running of the NASCAR all-star race.

As the major sponsor of the NASCAR Winston Cup Series when the Kulwicki Scholarship was first established, R.J. Reynolds made sure the announcement of scholarship winners was done in proper racing style. Some of the first winners were introduced to crowds prior to the running of the Coca Cola 600 in Charlotte, complete with several speeches from Charlotte Motor Speedway, RJR and UNC Charlotte representatives, and photos with Miss Winston. As the first Kulwicki Scholarship winner, Zeck got to ride into the track in a convertible with the NASCAR drivers prior to the running of the NASCAR all-star race.

Following the announcement of 2005 winner Terra Marckese, the UNC Charlotte representatives were feeling embarrassed when they had to walk up the front straightaway of the track to get to their seats. To their surprise, though, the fans cheered and waved at them the entire way.

Never one to be shy talking in front of people or at a loss for words, Johnson said he was awed when he had to speak before 150,000 people at one of the Kulwicki announcements. Rain was forecast for the day, and Johnson joked that he was ready with a lecture on thermodynamics to keep the crowd entertained if need be.

ICARA

A racing experience that was educational, exciting and fun during the early days of the motorsports program was intercollegiate auto racing. The brain child of Charlotte Motor Speedway President Humpy Wheeler, the college racing league was officially known as the Inter-Collegiate Auto Racing Association (ICARA).

Wheeler was a member of the UNC Charlotte Mechanical Engineering’s advisory board and also a friend of University of South Carolina engineering dean Craig Rogers. Wheeler envisioned a sport that would be the racing equivalent of NCAA football or basketball. The best way to get the sport started, Wheeler believed, was to start with schools that had engineering programs.

Wheeler was a member of the UNC Charlotte Mechanical Engineering’s advisory board and also a friend of University of South Carolina engineering dean Craig Rogers. Wheeler envisioned a sport that would be the racing equivalent of NCAA football or basketball. The best way to get the sport started, Wheeler believed, was to start with schools that had engineering programs.

“The ICARA concept kind of came out of South Carolina,” Hill said. “Craig Rogers and Humpy had the idea for a racing league. Rogers was a snake oil salesman, and nobody quite understood how he got things going, but he did. We ended up with seven teams.”

The college race teams were from UNC Charlotte, South Carolina, Old Dominion, N.C. State, Duke, Tennessee, and North Carolina A&T. The teams raced 5/8th scale Legends cars at tracks throughout the Southeast. Teams won points based on their finishing positions at each event, and the team with the most points at the end of the season was crowned national champion.

“I had to personally attend everything, which was a lot of time and work,” Hill said. “We won every year, though, and that was a lot of fun.”

The 49er team was dominant in ICARA because of the many experienced racers in the motorsports concentration. They knew about cars, they knew about race teams, they knew about setup and they knew how to drive. The team included a number of former go kart national champions.

“We had a bunch of kids with previous experience,” Johnson said, “and that was a huge advantage. They worked really well together as a team, which was really impressive. I’ll never forget the time in Virginia when it was a cold day and we had a major engine problem in qualifying. Those kids pulled the engine out of the car, did some major repairs, reinstalled the engine and got the car back out just in time for the race. I was impressed that they worked frantically, but worked together, and had it repaired in about an hour.”

“We had a bunch of kids with previous experience,” Johnson said, “and that was a huge advantage. They worked really well together as a team, which was really impressive. I’ll never forget the time in Virginia when it was a cold day and we had a major engine problem in qualifying. Those kids pulled the engine out of the car, did some major repairs, reinstalled the engine and got the car back out just in time for the race. I was impressed that they worked frantically, but worked together, and had it repaired in about an hour.”

The ICARA events were made up of three races. Each school had to use a different driver in each race. A qualifying heat determined the starting order for the first race. The UNC Charlotte strategy was to use one of their top drivers in qualifying in order to get a good starting spot in the first race. A less-experience driver would then drive the first race, usually from a good up-front position, which would lead to a top finish. For the second race, the field was inverted, meaning those that finished up front would be moved to the back. The 49ers used their most-experienced drivers who knew how to move through traffic for this race. For the final race, the team would again use a less-experienced driver who could run fast up front and stay out of trouble. The strategy worked, with the 49ers winning all five straight national championships between 1998 and 2002.

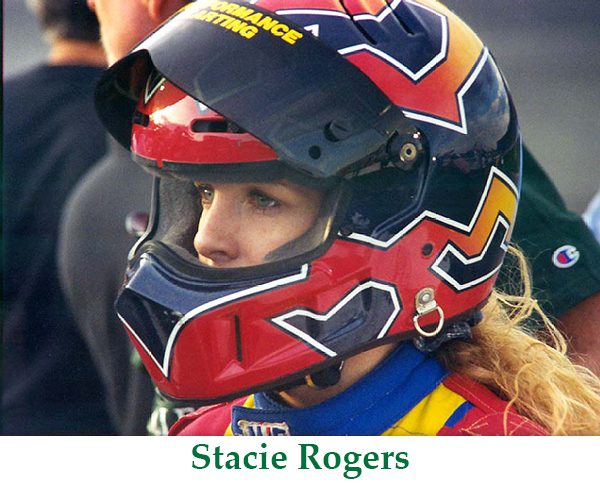

The 49er team was co-ed, with a number of female team members and drivers. The girls had as much experience and talent as the guys, and some had a much greater flare for the marketing side of the sport. During one year’s final event that was run prior to a major NASCAR race at Charlotte Motor Speedway, UNC Charlotte driver Stacie Rogers took the victory lap for the team, stopped on the start/finish line, jumped out of the car, pulled off her helmet and shook out her head of long blond hair to the cheers of the huge crowd.

The 49er team was co-ed, with a number of female team members and drivers. The girls had as much experience and talent as the guys, and some had a much greater flare for the marketing side of the sport. During one year’s final event that was run prior to a major NASCAR race at Charlotte Motor Speedway, UNC Charlotte driver Stacie Rogers took the victory lap for the team, stopped on the start/finish line, jumped out of the car, pulled off her helmet and shook out her head of long blond hair to the cheers of the huge crowd.

The ICARA league ended in 2002 when an economic downturn made it hard for the teams to find enough sponsorship to keep going. The 49er Legends team did stay together for a number of years, running in races at the Summer Shootout and Winter Heat series at Charlotte Motor Speedway.

Mini Baja

Another popular motorsports engineering project team throughout the years was Mini Baja. Sponsored by the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE), Mini Baja was a competition where engineering schools designed and built their cars from the ground up. The off-road vehicles were judged on static and dynamic criteria including an endurance race, hill climb, chain pull, maneuverability, suspension, presentations, written reports, and design presentations on the ergonomics, functionality and producibility of the cars. The endurance race could contain multiple obstacles, including crossing deep water.

Bob Hocken was the team mentor for the team for many years. The teams did much of their practice on his farm.

Bob Hocken was the team mentor for the team for many years. The teams did much of their practice on his farm.

“They used to come out to my place and we had course they could run through the woods,” Hocken said. “We set up cones for the obstacles course. By just practicing a couple hours they could cut their time to a third of what it was to start, just learning how to do the corners and such. It made a big difference.”

The first trip Hocken took with the team was to a competition in Florida. “We had no concept of what we had gotten ourselves into,” he said, “including how we were going to get across the water. All we had was a paddle. That was an experience.”

The team did have a number of successful years, including one where the 49ers entered two cars, which for a while were running first and second in the endurance event.

“We were running one and two for four hours,” Hocken said. “In the last 20 minutes one car blew a chain and came in fourth, so we finished first and fourth.”

Formula SAE

Formula SAE

The Formula SAE team was another design and build race team. Its purpose was for students to conceive, design and construct a high-performance formula-style race car to compete in the SAE Collegiate Design Series. Up to 120 international teams came together in the annual competition to compete in multiple events that tested the design and performance of their cars.

The 49er team was divided into a number of task groups including chassis, engine, suspension, aerodynamics and such. As part of the college’s senior design program, the groups worked for two semesters on the design and construction of their components. The team’s depth in motorsports experience and talented drivers led to a number of finishes in the top 20s.

NCMARC

Growth within the motorsports engineering program came in the form of increased research, as well as in undergraduate enrollment. To better organize and support this research, the Lee College of Engineering formed the North Carolina Motorsports and Automotive Research Center (NCMARC) in 2006.

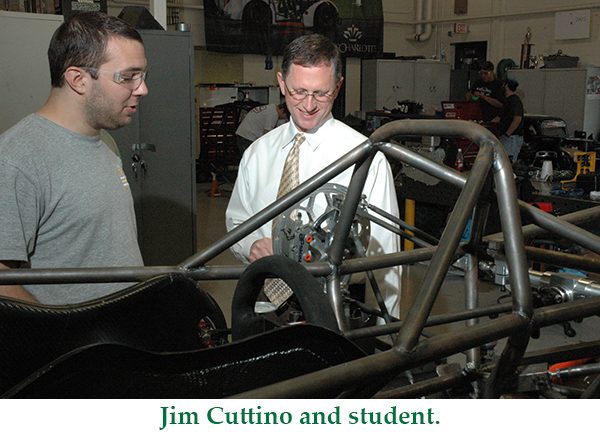

“When we started NCMARC, we hoped to hire a fulltime director to run it,” Johnson said. “We lost the money for that, though, so Jim Cuttino agreed to take it on and become the first director along with his other duties as a faculty member.”

With NCMARC in place, the motorsports program was successful in hiring a number of top researchers including Ahmed Soliman, David George, Peter Tkacik, Howie Fang and Mesbah Uddin. Research was conducted on a variety of levels, ranging from proprietary research for race teams to projects with the Department of Energy and undergraduate research. Research interest areas of the new NCMARC faculty included alternative propulsion systems, aerodynamics and fluids, and dynamics and stability.

With NCMARC in place, the motorsports program was successful in hiring a number of top researchers including Ahmed Soliman, David George, Peter Tkacik, Howie Fang and Mesbah Uddin. Research was conducted on a variety of levels, ranging from proprietary research for race teams to projects with the Department of Energy and undergraduate research. Research interest areas of the new NCMARC faculty included alternative propulsion systems, aerodynamics and fluids, and dynamics and stability.

With its core group in Mechanical Engineering, NCMARC also brought together more than 20 faculty members from other UNC Charlotte colleges and departments including Biology, Civil Engineering, Electrical Engineering, Engineering Technology and Chemistry. Their research areas included:

- Advanced Coordinate Metrology

- Advanced Powertrain

- Alternative Fuels

- Advanced Fluid Mechanics

- Advanced Surface Metrology

- Bearing Design and Lubrication

- Computational Fluid Dynamics

- Computational Methods in Engineering

- Conduction Heat Transfer

- Convection Heat Transfer

- Deformation and Fracture of Materials

- Engineering Metrology

- Experimental Stress Analysis

- Finite Element Analysis and Applications

- Fundamentals of Heat Transfer and Fluid Flow

- Mechanical Behavior of Materials

- Mechanical Design

- Mechanism Analysis

- Mechanism Synthesis

- Theory of Elasticity

- Tribology

- Vibrations of Continuous System

Facilities

The motorsports engineering program started out is a small, crowded lab on the first floor of the Smith Building. The program was very successful in building and expanding into the new facilities it needed for its undergraduate and research programs.

The first purpose-build motorsports facility was the 6,800-square-foot Motorsports Engineering Laboratory, which opened adjacent to the new Duke Centennial Hall in 2006. The lab provided the necessary space for the FSAE, Legends, Baja and other teams.

The first purpose-build motorsports facility was the 6,800-square-foot Motorsports Engineering Laboratory, which opened adjacent to the new Duke Centennial Hall in 2006. The lab provided the necessary space for the FSAE, Legends, Baja and other teams.

Equipment in the lab was comparable to that of professional race teams, which helped give students the hands-on experience they needed to land good jobs. The equipment included engine and chassis dynamometers, a FARO data acquisition system, a flow bench and computer design facilities.

On Oct 13, 2009, UNC Charlotte renamed the lab the Alan D. Kulwicki Motorsports Laboratory in honor of Kulwicki. The Kulwicki family had made a large gift to the program to fund more equipment for the lab and scholarships for students.

The next new motorsports facility opened in January of 2012. The 16,500-square-foot $4.5-million Motorsports Research Building brought much-needed space for increased research and graduate studies. Research equipment in the new building included a water tunnel, wind tunnel, alternative propulsion dynamometer test cell, computational labs, as well as faculty and graduate student offices.

At the same time, the Lee College of Engineering named Mesbah Uddin as the new director of NCMARC. Uddin had come to UNC Charlotte in 2008 from Chrysler Dodge Motorsport, where he supported their NASCAR Cup program. His research interests included aerodynamics of race and passenger cars, flow inside human airways, and experimental and numerical investigations of wakes, jets and boundary layers.

At the same time, the Lee College of Engineering named Mesbah Uddin as the new director of NCMARC. Uddin had come to UNC Charlotte in 2008 from Chrysler Dodge Motorsport, where he supported their NASCAR Cup program. His research interests included aerodynamics of race and passenger cars, flow inside human airways, and experimental and numerical investigations of wakes, jets and boundary layers.

“Before Motorsports Research opened we had no place for graduate research work at all,” Uddin said. “The building allowed the graduate program to grow, which was its biggest contribution. By 2014 we had 20 grad students.”

The excellent motorsports facilities were also important in attracting new students at the undergraduate and graduate levels, Uddin said. “Whenever we gave tours to prospective students, very rarely did they not want to come here,” he said. “We gave them a tour and they told me ‘I’m coming here.’ The message I heard over and over was our facilities were pretty much unparalleled.”

Later Years

By 2008, the motorsports engineering program had reached a record enrollment of about 110 students. With the economic downturn that year, though, race teams started cutting jobs. Realizing this, fewer and fewer students went into the motorsports concentration.

“We had a steady decline in students for a few years,” Uddin said. “Teams were cutting positions and not hiring new people. The automobile industry was hit hard. And about one-third of our students had always been from out of state, and it was more difficult for them to pay their higher tuition.”

“We had a steady decline in students for a few years,” Uddin said. “Teams were cutting positions and not hiring new people. The automobile industry was hit hard. And about one-third of our students had always been from out of state, and it was more difficult for them to pay their higher tuition.”

Enrollment hit its lowest level in 2011-12, when there were only 75 students in the program. A steady increase then began as the economy rebounded and by 2014 enrollment reached a new high of 115. Projections were for 125-130 students in 2015, and 150 students in 2016.

From 2008 to 2015, the number of Mechanical Engineering masters and Ph.D. graduates who focused their research on motorsports and automotive engineering continued to grow. By 2015, 40 students had graduated in motorsports concentration areas.

“We began seeing more interest from engineers on race teams wanting to come and do a graduate degree on a part-time basis,” Uddin said. “So, we created more courses that were flexible in terms of when they were offered, which allowed professionals to get their graduate degrees while they continued working.”

In its later years, the program began to offer more courses in computational analysis in response to race team needs. “A lot of teams were relying hugely on vehicle and aerodynamic simulations,” Uddin said. “They were looking to us for students with strong analytical skills. We began offering more courses and projects that had a component of analytical skills involved. We added courses in finite element methods, vehicle dynamics, aerodynamics, tire dynamics, and motorsports instrumentation. We offered all the courses required to make someone a good race engineer.”