Advancing 1982-1998

UNC Charlotte and its College of Engineering grew steadily in programs, students and facilities from 1965 to 1982. The next step in the evolution of the university and the college was to now start doctoral programs, create more master’s programs and build the research initiatives that would make these advanced degree programs possible. To this end, UNC Charlotte declared the strategic goal of achieving the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching classification of Doctoral Research Intensive within the next 10 years. The College of Engineering would be a key player in making this happen.

“A cultural change was taking place,” Snyder said. “Research credentials were becoming more and more important to promotion and tenure across the country. If we wanted to hire top-notch professors from outside, or just be competitive with faculty coming out of top schools, we had to have top research programs. It was either do research and provide that research environment or die on the vine.”

With no existing research programs of any significance, College of Engineering leaders began looking for areas where the college could serve the research needs of the community and the state. They also looked for research areas that could take advantage of opportunities and work angles in conjunction with other initiatives that were already well funded and could bring money and faculty positions to UNC Charlotte.

“That’s how we operated at the time,” Snyder said. “Any way we could skin a cat. A lot of the time we were making deals at the state level on our own, without going through official university channels. I have to thank Chancellor Fretwell for just getting out of the way. He always acted surprised after it was done, but he knew what was going on and he let us do our thing.”

A major partnering opportunity the College of Engineering was able to capitalize on was the creation of the Microelectronics Center of North Carolina (MCNC), which gave a huge jump start to the college’s research efforts in 1982.

MCNC

As a statewide federally funded effort, organizers conceptualized MCNC as the Silicon Valley of the east. Those involved in the initial planning for MCNC were Research Triangle Park, North Carolina State, UNC-Chapel Hill and Duke University.

“We squeezed in when the opportunity was there,” Snyder said. “North Carolina A&T had been added to the mix, because the federal funding required that a minority institution had to be involved. We had better credentials than A&T, so they had to let us in too. That’s how we became the fifth school. It was another way of skinning the cat.”

The physical facility for MCNC was constructed in Research Triangle Park, between Durham and Raleigh, North Carolina. The federal funding established a number of distinguished professorship positions for the universities involved. The concept was that the new distinguished professors would work part-time on their research at the MCNC facility, and then teach and do some additional research at their institutions. The faculty member that UNC Charlotte hired through this arrangement was Edward Nicollian.

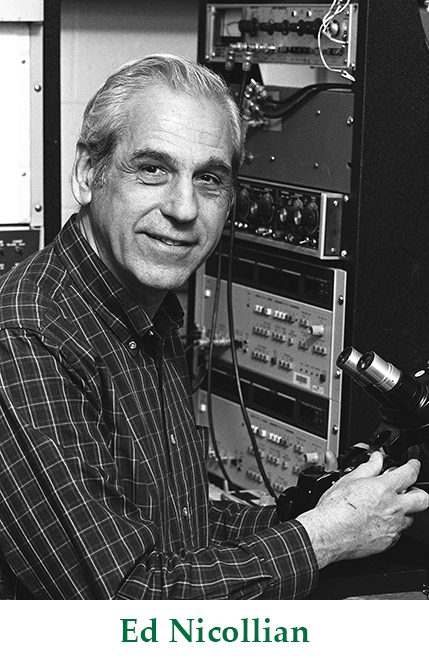

Ed Nicollian

“MCNC wanted to hire all these real international hot shots of which Nicollian was one of the best,” Snyder said. “Nicollian didn’t have a PhD, he was not Dr. Nicollian, which was a stumbling block to getting him tenure or a full professorship at Duke or NC State, but not at UNC Charlotte. At least I didn’t make it a stumbling block. It was a real coup for sure to hire Nicollian. With him came all the trappings that we were now doing first-class research. Getting him eventually led to hiring a whole string of outstanding faculty.”

A colleague of Nicollian’s who did follow him to UNC Charlotte a few years later was Dr. Raphael (Ray) Tsu. Nicollian was one of the top electrical engineering researchers of his time, Tsu said, because of his work at Bell Labs on transistors.

“Without Nicollian there wouldn’t be transistors,” Tsu said, “because Nicollian made the mosfet (metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor) work. He developed the method to find defects (trapped current) in the material.”

Another of Nicollian’s notable achievements was the invention of the Q-C method for MOS measurements.

Farid Tranjan of Electrical and Computer Engineering worked with Nicollian on research at MCNC.

“He had very gregarious personality,” Tranjan said. “The first time I met him was at his interview and he looked horrible. He had poison ivy everywhere. I enjoyed working with him. He was full of life, very energetic, and a genuinely nice person. But you had better not cross him.”

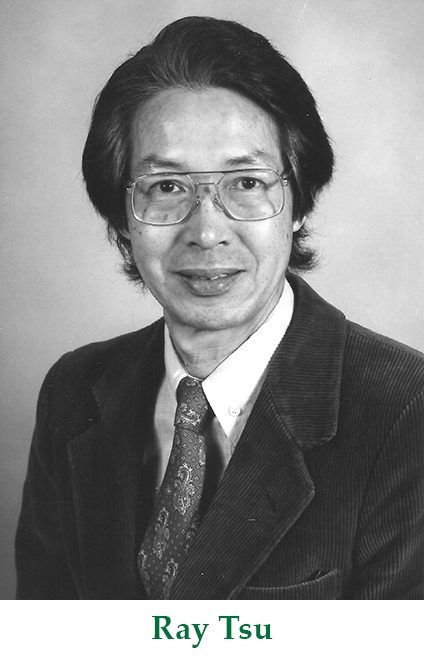

Ray Tsu

Tsu and Nicollian had worked together for a number of years, first at Bell Labs and then at MCNC where they shared an office in 1987. Tsu was at North Carolina A&T, having been recruited as its distinguished professor for the MCNC initiative. Nicollian felt the two of them could work better together, though, if Tsu was at UNC Charlotte. There wasn’t an appropriate electrical engineering position open at UNC Charlotte, so some creative hiring tactics involving the university’s top people were needed.

“It was a Friday afternoon at four o’clock,” Tsu said “Nicollian called me and said ‘Come be my house guest tonight, tomorrow we’re going to see (Chancellor) Fretwell. He said ‘You should do it’. So I went and at 10 o’clock on Saturday we went to Fretwell’s house. He told me ‘Ed called me on the phone and said he is suffocating. I don’t want Ed to suffocate. I asked him what he had in mind and he said he wants me to hire you.’”

They shook hands on the deal and then went to Fretwell’s office on campus to work out the details. Fretwell called in Vice Chancellor of Academic Affairs James Werntz Jr. Werntz had the paperwork for Tsu to take a precision engineering position in the Mechanical Engineering Department. When Tsu said he was an electrical engineer, Werntz told him not to worry about it that they would find him another position later.

“Then Werntz asked Fretwell if he could use his phone and he called Snyder,” Tsu said. “So we met with Snyder that same day. He told me I would have to officially meet with the department faculty on Monday, but it was a done deal. Snyder took over at that point, negotiating money to build my lab and such, and he gave me money for a Ph.D. student and a post-doc position.”

So in the space one long weekend, at the urging of Nicollian, UNC Charlotte had hired another top researcher in the field of electrical engineering. Tsu had been instrumental in developing the ultrasonic amplifier at Bell Labs, and from there had moved to the IBM T.J. Watson Research Center in New York. It was there that he began his well-known collaborations with Dr. Leo Esaki, working on the theory of man-made quantum materials, quantum wells and superlattices.

By his theoretical calculations, Tsu proved that quantum states could be designed in multiple layers of semiconductors in a superlattice structure. He provided the basic theory of negative differential conductance applicable to the man-made Superlattice, and then he achieved tunneling through the double barrier structure. These results formed the forerunner of today’s nanoelectronics. Tsu became known as the “Superlattice Man.”

The other person whose position was involved in the maneuvering that brought in Tsu was Robert Hocken, who would be a central figure in building the College of Engineering’s Center for Precision Metrology and the college’s doctoral programs. Hocken was hired in the actual distinguished professorship that was open at the time, and came in as the Norvin Kennedy Dickerson Jr. Distinguished Professor of Mechanical Engineering in 1998.

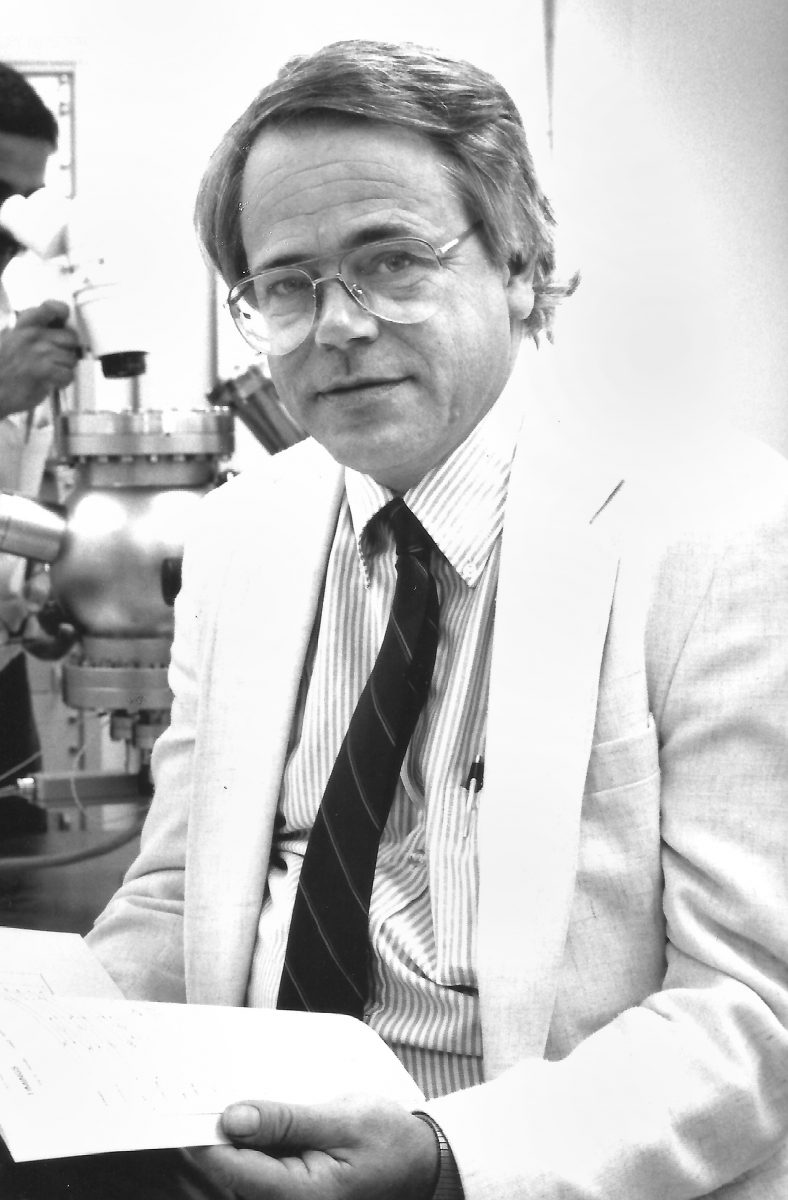

Bob Hocken

One of the people who can be credited with recruiting Hocken was Engineering Technology professor John Patten, who was on a committee planning a new research building for engineering. “I was the technical expert on infrastructure needed for the labs and shops,” Patten said. “I was also the only precision engineering person here at the time. With Kodak coming to Charlotte (see Cameron Center below for details) the precision engineering component of research had become very important.”

The committee decided it would use the Dickerson distinguished professorship to recruit a top-level precision engineering researcher. In asking leading people in the profession who the best person to hire would be, the name they kept hearing was “Bob Hocken.”

“But whoever we were talking to would say ‘You’ll never be able to get him,’” Patten said, “but we did get him.”

Hocken was the former chief of precision engineering at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and one of the most respected experts in the world in precision engineering and metrology. Incentives that persuaded him to come to UNC Charlotte included the opportunity to build a research program from the ground up and the chance to be part of a new research building, the Cameron Center, which would have purpose-built laboratories for his specialized area of research.

“The building of the Cameron Center was definitely part of the reason I came,” Hocken said. “There wasn’t much university support for research at the time, but I had been promised $1 million in startup for equipment and such, and a home in the Cameron Center.”

When foundation workers hit solid rock during Cameron’s construction, cost overruns quickly mounted and about $500,000 of the money promised Hocken was taken to finish the building. “We did have enough to buy some measuring machines and other stuff,” Hocken said, “and were able to get the lab started.”

C.C. Cameron Applied Research Center

Another major initiative the College of Engineering was able to take advantage of in the building of its research programs was the recruiting of Kodak to Charlotte’s University Research Park. For economic and marketing reasons Kodak would never open its proposed manufacturing facility here, but opportunistically, UNC Charlotte was able to get a new building, the C.C. Cameron Applied Research Center, out of the deal.

The plan for recruiting Kodak started with Seddon “Rusty” Goode Jr., who was then president of the University Research Park. Goode’s successes in bringing technology businesses to the park were numerous, and in the mid-1980s he saw the chance to recruit Kodak. He understood the value of strong university research support in recruiting high-tech companies and he looked to the College of Engineering to provide that support.

The proposed Kodak facility would include manufacturing and research capabilities in the production of 14-inch optical storage disks. The 14-inch disks would be a larger version of the more common CD-ROM disks, and would possess tremendous data storage capabilities in the new field of optical recording. With Goode providing leadership, a diverse team of educators, politicians, business leaders, scientists and engineers joined forces to develop strategies for dealing with governors, senators, legislators, CEOs, university presidents, local commissioners, tax administrators and numerous others.

“Kodak agreed to bring their facility down here if the state would build a research center at UNC Charlotte and a technology building at CPCC,” Snyder said. “The stipulation for a new research buildings had actually been at our request. We told them we can’t work with you if we don’t have the facilities, so you have to request them from the state.”

A key meeting to outline the strategy for winning budgetary support for the new buildings was held with Rusty Goode, a few key people from Kodak, UNC Charlotte and CPCC, and State Senator Kenneth Royall. Royall, a Democrat, was one of the most powerful people in the North Carolina legislature and could garner support across party lines.

“The only people who knew about the deal were the people in that room,” Snyder said.

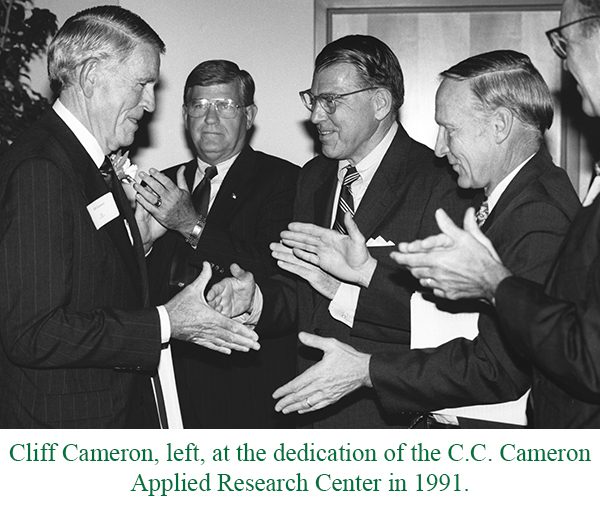

Goode and Royal had the political clout to get a funding package for the buildings attached to the state budget for 1987-88 and passed through the legislature. The missing piece was Republican Governor Jim Martin, who could easily kill the project if he was against it. The person who was able to win Martin’s support was Charlotte business leader Cliff Cameron. Cameron had been a bank CEO, served on the UNC system and UNC Charlotte leadership boards, and was Gov. Martin’s budget officer.

“I can’t go into the details about how it was done, but it was done,” Snyder said. “The president of CPCC and Fretwell didn’t know anything about this deal, cause they weren’t at the table. So the legislature went into session and the bill went to the Governor. It was the middle of July and the budget was passed. I got a call from the vice chancellor of financial affairs for the University of North Carolina system, and he said ‘We just got the budget from the legislature and it contains a building for Charlotte. Do you know anything about this?’ I said ‘No, I don’t know a thing about it. But it’s wonderful, a building in the budget for us?’”

With funding approved, UNC Charlotte immediately began plans and designs for the new research building. On the academic side, they developed curriculum to educate engineers in optical technology. The key players from the project, and the somewhat surprised leaders of the university, broke ground for the building on Sept. 23, 1988.

“At the groundbreaking I said, ‘This building wouldn’t be here without Rusty Goode,’” Synder said. “That was the truth. He did it. He made it happen.”

CPCC was also progressing with its new technology building and the creation of new courses to train technicians. On the State of North Carolina’s side, everything was falling into place to support the Kodak 14-inch disk manufacturing project. On the Kodak side, though, economic forces and new technologies were working against the project. When introduced to the market in 1988, response to the 14-inch disks had been favorable. By 1990, though, less-expensive and more-convenient 3.5-inch floppy disks were quickly gaining popularity. On March 20, 1990, Kodak announced it was selling its optical storage business. It was the end of the Kodak project in University Research Park.

Kodak repaid North Carolina for non-recoverable money the state had spent in support of the project. It did not have to reimburse the state for items that would remain as state assets, which included the new research building at UNC Charlotte.

Dedication of the new building was on Sept. 25, 1991, when it was officially named the C.C. Cameron Applied Research Center. Cliff Cameron, the building’s namesake, had been important to the creation of the building and for many years had been a key leader in higher education in North Carolina. Cameron’s list of achievements and service included chief executive officer of First Union Corporation, chair of the UNC Charlotte Board of Trustees, chair of the UNC Board of Governors, chair of the University Research Park, budget officer for the State of North Carolina, and board member of MCNC.

When it opened its doors in 1991, the stated mission of the 75,000-square-foot Cameron Center was to build programs in fundamental areas of applied research. The four cornerstone technologies would be:

- optoelectronics and microelectronics

- precision engineering and computer integrated manufacturing

- biotechnologies, and environmental engineering and science

- transportation engineering and planning

In addition to the science and technology research programs originally created to support Kodak, the building also housed the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute, the Center for Business and Economic Research, and the Engineering Research and Industrial Development Office.

John Hudak came to the Cameron Center in 1994 to supervise the building’s clean room facilities. He had spent the previous 20 years in California working on microelectronics with for an aerospace facility.

“The Cameron Cener was the university’s primary research facility,” Hudak said. “When it opened it was just a shell. When I came in ’94 they were still struggling to fill it. There wasn’t much equipment and a lot of what we did have was donated. It was kind of run on a shoestring.”

Purpose-built metrology laboratories with precise temperature, humidity and vibration control were on the building’s first floor. A 3,500 square-foot, class-10,000 clean room was on the second floor.

In the first years of the Cameron Center, some of the electrical and optical researchers working with Hudak in the clean room included Ed Nicollian, Ray Tsu, Mike Feldman, Steve Bobbio, Kasra Daneshvar, Dick Green, Mohamed-Ali Hasan, Art Edwards, George Metz and Jack Chaffin.

Serving as interim director when the Cameron Center first opened was Jack Roblin, who then moved to the position of industrial liaison. The first permanent person hired to lead the Cameron Center was Harry Leamy, a materials scientist from Bell Labs.

“They wanted to hire a more visible person to run the new research center,” Tsu said, “and hired Harry Leamy. Harry was an old friend of mine. He also came from Bell Labs. Harry’s plan was to enlarge the clean room and he succeeded in getting it to the size it is today. We worked a lot together over the years deciding the best ways to use our limited resources.”

When Leamy arrived in 1992, the first floor of the Camron Center was about 50 percent occupied and the second floor 20 percent. Leamy built an external advisory board to craft a mission for the center that would help it grown in research areas that supported the community. By 1995, there were 175 projects underway and the Cameron Center was full to capacity.

One of the strongest programs from the outset of the Cameron Center was the precision engineering and metrology group led by Bob Hocken. Hocken had started an affiliates program of industrial partners, which was bringing projects and money to the precision group. In 1997, the State of North Carolina designated the group as the state Center for Precision Metrology. In 1998, the National Science Foundation named the group an Industry/University Cooperative Research Center program. (For more information on the precision engineering and metrology program see the section on ‘The Centers’ and chapter on ‘Center for Precision Metrology.’)

Another important Cameron Center research area that involved engineering was in the field of biomedical engineering. Combining faculty from engineering and biology, this interdisciplinary group of researchers was collaborating in areas such as tissue engineering, cryo storage, biopresevartion, molecular engineering, medical technologies and biomechanics. External partners included Carolinas Healthcare System, Presbyterian Hospital and Ortho Carolina, as well as other university bioengineering research organizations. In 2005, the group became the Center for Biomedical Engineering Systems. (For more information on the biomedical engineering program see the section on ‘The Centers’ and chapter on ‘Center for Biomedical Engineering and Science.’)

With its research programs and projects growing quickly, it wasn’t long before the Cameron Center needed more space. In 1999, UNC Charlotte leaders approved a 35,000-square-foot expansion that would add 50 percent more research space to the building. The $4.5-million expansion was completed during the next 18 months.

Research and academic facilities on the UNC Charlotte campus grew steadily in the following years, and the Cameron Center continued to evolve. With the construction of Woodward Hall, Grigg Hall and the Energy Production and Infrastructure Center, many of the electrical and optical engineering researchers moved out of Cameron. The construction of Duke Centennial Hall saw the exit of the Center for Precision of Metrology from Cameron.

As of 2015, the primary campus clean room still remained in Cameron and was used for undergraduate education, as well as graduate programs and faculty research.

“In 2000 we started teaching freshman-level electrical engineering in the clean room,” Hudak said. “It gave the freshmen a hands-on experience early in their studies and got them excited about engineering. They loved to do the hands-on projects instead of just sitting in classroom.”

Graduate Programs

Along with essential state-of-the-art laboratories and equipment, the other key component to building research in the College of Engineering was the establishment of graduate degree programs. For faculty to win the grants they were pursuing and then do the research, they had to have graduate students to support them.

Snyder had been instrumental in planning the college’s Master’s of Science in Engineering program when he first came to the college in 1975. The program crossed departmental lines, and bachelor’s students from any engineering discipline could take part. It took several years for the university and the state to grant the program full approval. In 1979, the first Master’s of Engineering classes began.

By the mid-1980s, engineering leaders began planning degree-specific master’s programs for their individual departments. These won approval, and in 1987 individual master’s of science degree programs started in Civil Engineering (MSCE), Electrical Engineering (MSEE) and Mechanical Engineering (MSME).

The next step in the evolution of graduate programs was the creation of doctoral degrees.

“The pressure to establish the Ph.D. programs came from engineering,” Snyder said. “The university was pushing us to do research, and we said ‘Look, we have to be able to get Ph.D. students. Faculty can’t do research without students.”

In the late-1980s there had been some creative cooperative Ph.D. programs designed to put doctoral students on the UNC Charlotte campus, but none of them lasted very long. One such program had students at the College of Engineering doing research here as part of Ph.D. programs with universities in England, France and China.

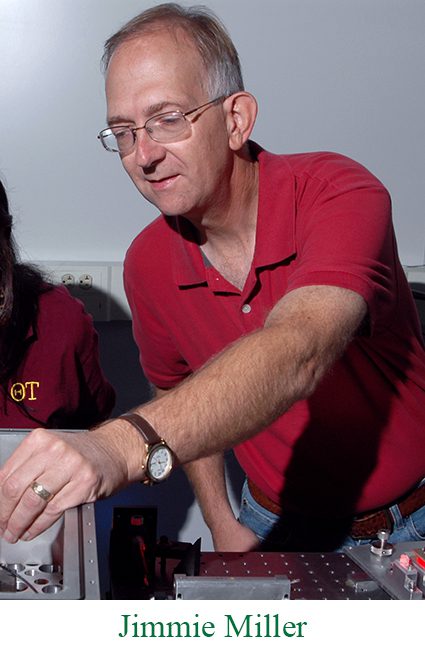

Jimmie Miller, who would go on to a career in the UNC Charlotte Center for Precision Metrology, was one of four students who took part in these international doctoral programs. He completed his studies and research in Charlotte for his doctoral degree from the University of Warwick in England.

“It was a cooperative program where I was enrolled as a student there and did my research here,” Miller said. “With the European programs, all of your study was rolled into your research. There was no classwork.”

Miller did a three-month visitation to Warwick as part of the program, but that was his only time in England. He graduated in 1994.

Another cooperative program attempting to bring Ph.D. students to Charlotte was an interinstitutional doctoral program between UNC Charlotte and N.C. State that started in 1986. Students did mostly classwork in Charlotte, and then took more classes and worked on research projects for faculty mentors in Raleigh. The degree itself was ultimately from N.C. State.

Two students who participated in the N.C. State interinstitutional program were Johnny Graham and Helene Hilger, both of whom became Civil Engineering faculty members at UNC Charlotte.

Graham worked as a teaching assistant at UNC Charlotte while completing his degree. “I was taking classed here and in Raleigh, driving there two days a week, and then back here at night to teach,” Graham said. “My commencement was actually held at the old Charlotte Coliseum. I have the first and only Ph.D. conferred at a UNC Charlotte commencement in the old coliseum. “

Hilger pursued her Ph.D. with the aid of a Target of Opportunity Program (TOPs) federal grant. Through the program, she taught 20 hours a week at UNC Charlotte and took classes at both Charlotte and N.C. State. It took her five years to finish the doctoral program, graduating in 1998.

The cooperative doctoral programs did generate a few Ph.D. engineering students for UNC Charlotte, but not in the numbers that the College of Engineering was looking for.

“The program with State was actually a nightmare,” Snyder said. “It was hard on the students, and N.C. State was getting all the research.”

“The joint N.C. State degree was bleeding our students out,” Farid Tranjan said. “We knew we had to get our own Ph.D. degrees to open the doors for recruiting the right people. It was very important for our future.”

Tranjan teamed up with Paul DeHoff of Mechanical Engineering and Ellis King of Civil Engineering to write the first proposal for a Ph.D. in engineering at UNC Charlotte. Their initial proposal was for a single program that wouldn’t be specific to any engineering discipline. Chancellor James Woodward rejected the idea.

“Woodward said ‘No,’ we had to split it up into discipline-specific degrees,” Tranjan said. “So, we rewrote the proposal for separate Ph.D.s in civil, electrical and mechanical engineering. The problem then was that the university only felt it could get three Ph.D. programs approved by the state, so they shouldn’t all be in engineering.”

“Woodward was an engineer,” Snyder said, “so politically he couldn’t push just engineering Ph.D.s. So, he bumped our Civil Engineering Ph.D. and added math. He felt he could only get three approved, and so politically he had to have something from arts and science.”

Civil Engineering did have some very strong research at the time and was upset at getting dropped from the doctoral proposal. “They did have some good people doing research in transportation,” Snyder said “But they didn’t have a Nicollian or a Hocken.”

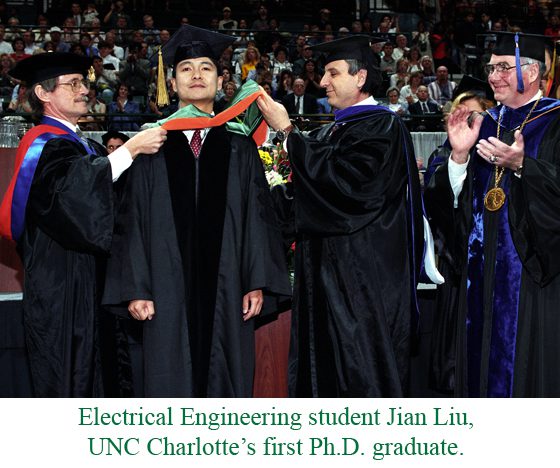

The UNC General Administration approved UNC Charlotte’s first doctoral proposal, and in 1993 Ph.D. programs started in Electrical Engineering, Mechanical Engineering and Mathematics. The College of Engineering conferred the first doctoral degree in the history of UNC Charlotte in 1997 to Electrical Engineering student Jian Liu.

“It was a monumental event,” Snyder said, “not just for the college, but for the university. It put us on a different standing among universities. We were not a full-fledge research university yet, but we were a doctoral university. It was a feather in the college’s cap to be the ones who led the way.”

It wasn’t until 2004 that Civil Engineering got a doctoral degree program. The department was instrumental in creating the interdisciplinary Infrastructure and Environmental Systems (INES) doctorate. The program focused on the interrelationship between infrastructure and the environment at the systems level. The majority of the first students were from Civil Engineering, but there was also participation from Geography and Earth Science, Biology and Chemistry. The interdisciplinary nature of the program proved to be a strength over the years, bringing together students and faculty from non-traditional areas to collaborate on successful research.

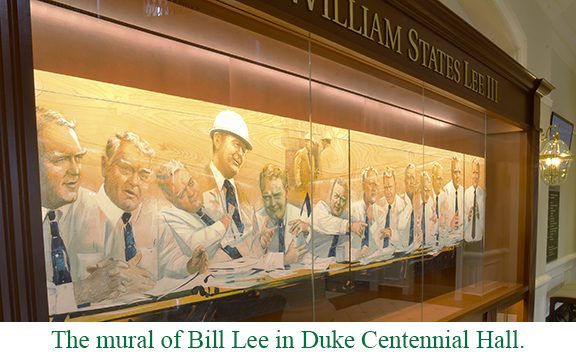

Bill Lee

From its very beginnings, the College of Engineering had a close relationship with Duke Power Company, which later became Duke Energy. One of the principal figures in the history of Duke Power and the College of Engineering was William States Lee III – Bill Lee.

Born in Charlotte in 1929, Lee was the grandson of William States Lee Sr., who helped found Duke Power and was its first chief engineer. During his early career in the late 60s and early 70s, Lee III was instrumental in the design, engineering and construction of Duke’s nuclear power plants.

In 1976, Lee became executive vice president of Duke Power. He was named president and chief operating officer in 1978, and chairman and chief executive officer in 1982. Lee was a national and international leader of the nuclear power industry. In 1979, the Institute of Nuclear Power Operations was formed and Lee served as its chairman from 1979 to 1982. The World Association of Nuclear Operators was founded in 1989, and Lee served as its president until 1991.

Lee’s first involvement with UNC Charlotte’s College of Engineering was as a member of Newton Barnett’s advisory board. Lee also made the time to speak to College of Engineering classes.

“Bill Lee was on our advisory board before he was head of Duke,” Jack Evett said. “When I started here I was teaching freshman engineering and Bill Lee would come out and talked to the class. He really wowed them.”

Lee’s influence throughout Charlotte, in both the engineering industry and the overall community, made him a strong ally of the College of Engineering.

“I cultivated a personal relationship with Bill Lee,” Snyder said. “Whenever I had a political or financial problem, I talked to Bill eyeball to eyeball, engineer to engineer, and he helped me figure out a way to do it. He and I were on the same wavelength.”

The relationship also worked both ways, and Lee used his influence with Snyder to create the type of engineering education he believed it was important to teach at UNC Charlotte. He actively promoted integration and associated programs, was a great believer in the importance of a strong liberal arts component in engineering, and was a proponent of international education.

“So, these were things I began championing,” Snyder said. “And Bill Lee always backed me up. He was willing to help and he did help.”

To honor Lee’s commitment and long involvement with the College of Engineering, the UNC Charlotte Board of Trustees made the decision to name the college after him. On March 31, 1994, the College of Engineering officially became The William States Lee College of Engineering.

At the dedication ceremony, Russell Robinson II, chairman of the Board of Trustees said – “A university has many ways to honor its alumni and supporters; honorary degrees, names on rooms, laboratories and buildings, names on scholarships and professorships. UNC Charlotte has already awarded Bill Lee an honorary doctorate. Today, we announce what I believe is the highest honor of all, the naming of The William States Lee College of Engineering of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.”

In his remarks at the dedication, Woodward said – “In naming the college for Bill Lee, we have solidified a relationship between two institutions that has certainly served UNC Charlotte well, and I hope, has served Duke Power well.”

In Bill Lee’s personal remarks at the event, he expressed his feelings in the words “grateful, excited and hopeful.” For the word “hopeful”, he said – “Hopeful that this college of engineering can flourish in exceeding the expectations of this dynamic region in providing educated engineers and push the frontiers of applied research that is both essential to undergird the quality of growth that I see coming in what is internationally recognized as the economic capitol of both Carolinas, and an opportunity for the college to be interactive with the region in mutual support. For such a future, I’m much more than hopeful, I am absolutely confident!”

Snyder, addressed his remarks at the event to Bill Lee personally, saying – “This event is a major milestone in the development of our college and could not have occurred at a more fortuitous time. We are in the midst of developing our college’s blueprint for the future. What better person to serve as a beacon to guide us in this effort than our new namesake, Bill Lee.”

Part of the blueprint for the future that Snyder mentioned was a plan to bring some of the science departments at UNC Charlotte into the newly named William States Lee College of Engineering. By uniting the resources and strengths of engineering and science, Lee and Snyder felt the resulting combination would have more success in securing and accomplishing research.

“Lee and I had become very close,” Snyder said. “He had a plan to bring math, chemistry and physics into a joint college of engineering and science. This would help us compete for big research dollars. We would be able to work better together, and there would be less bureaucracy and paperwork. Clemson had just done this and had gone from 99th in research to 15th. But Woodward would have none of it.”

Another of Lee’s and Snyder’s goals for the future was to integrate more liberal arts and international studies into the engineering curriculum. This goal also never happened, because of Lee’s sudden death in 1996 at the age of 67.

“The day before he had his heart attack I was in his office that morning,” Snyder said. “I’ll never forget that we shook hands on a deal that I would stay on as dean as long as he would stay on with the project we were going to do, which was the strategic plan to formalize some of these ideals on liberal arts studies and international studies. He would provide the financial and political pressure to get it done. Then he had to go catch a plane. He died of a heart attack that day in New York. It was the most disastrous day of my career. I kind of lost heart after that, because we had some great plans to implement and that all went down the tubes.”

Computer Science

The integration of some of the sciences and math into engineering never happened in the 1980s, but earlier in the history of the College of Engineering a new department had been created and established. The new field of computer science was growing by leaps and bounds, and area industry was desperate for trained professionals. So in 1985, UNC Charlotte created the Department of Computer Science within the College of Engineering.

UNC Charlotte had a few faculty members in the math department who were interested in computers, and they were offering a specialization in computers as part of the math degree. These faculty members transferred to engineering to become the nucleus of the new Computer Science Department.

“It was going to be a hot area, everybody saw this,” Snyder said. “I thought the best way for it to grow was to put it in the College of Engineering where I had the resources to feed it. The half dozen or so faculty from math moved to engineering and eventually formed the Computer Science Department.”

Shortly after its creation, the new department created a bachelor of arts degree program and bachelor of science degree program in Computer Science. (For more information on Computer Science and its evolution to the School of Information Technology and then to the College of Computing and Informatics see our “Computer Science” chapter.)

International Studies and Cooperative Education

Snyder and Lee’s vision for a large international studies program that would be tied into engineering curriculum was never realized, but the College of Engineering did have a moderate international program established with several European universities.

Norm Schul had moved from his position as leader of Geography and Earth Science into a centralized university support position in 1980. Part of his job was to build and establish new programs for the university and the colleges.

“Snyder asked me to work with engineering to do international exchanges and international research,” Schul said. “We got funding to build international coops and faculty exchange programs to support research. We made some visits to European universities and established several successful exchange programs.”

The first exchange programs were with universities in Aachen, Germany; Santander, Spain; Limoges, France; and Bethune, France.

“Bethune was the one that really took off,” Schul said. “We started sending students there and them here. We were exchanging about five or six faculty a year. They loved coming to Charlotte. What developed here was a fine program that gave a real engineering experience.”

There were a number of language and cultural problems, but that was part of the learning experience. “A real eye opener for me was how amazed the students from France were about truly being part of a research team,” Schul said. “In France everything came from the top down and a student made no decisions. Here they were included and empowered to figure out on their own the best way to do things. They really liked that.”

Another of Schul’s special tasks was to expand the experiential learning program of coops and internships that David Bayer had started in engineering. They worked together for about a year, while also keeping up with their other responsibilities. The program became so successful, though, that Snyder decided it needed to be an actual office of the college with a dedicated director. He offered the job to Schul

“So, I moved over to engineering,” Schul said. He was in the position for about six years, creating a number of programs with area engineering companies. One of the most active programs was with Duke Power.

“In 1993, the coop stuff was transferred to the University Career Center,” Schul said, “and I was out of a job again. But we had built a very successful program. The students learned a lot and got a lot of real-world experience. The companies got the opportunity to try out some students and hire some good employees.”