Civil and Environmental Engineering

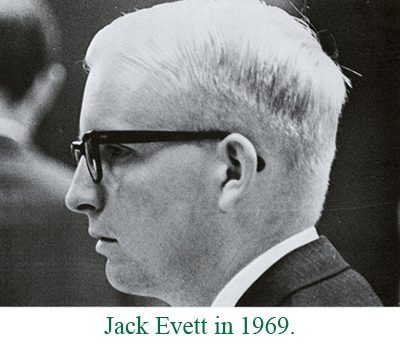

As a discipline, civil engineering dates back thousands of years to the pyramids of Egypt and aqueducts of Rome. As a program at UNC Charlotte, civil engineering got its start in 1967 when faculty member Jack Evett arrived. Evett was the sixth member of the college of engineering faculty and the first in civil engineering. There were about 100 engineering students at the time, out of a total of 2,000 overall students on the UNC Charlotte campus.

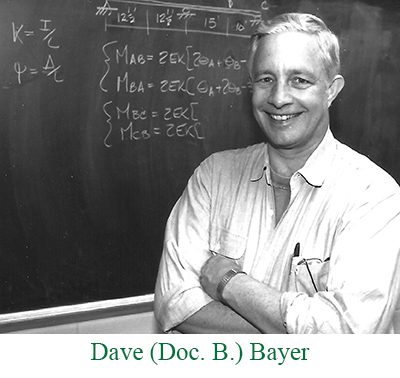

The second UNC Charlotte Civil Engineering faculty member was David Bayer. “In 1968, I was a first lieutenant in the US Army Corps of Engineers stationed at the US Army Waterways Experiment Station in Vicksburg, Mississippi,” Bayer said. “Late that year I replied to an ad to Dr. Newton Barnette, chairman of the UNC Charlotte Engineering Division, about an opportunity for a structural engineer position. I never got a response to that letter. A year later, now a Captain and about to finish my military commitment, I wrote again … I am not sure why.”

Bayer got the job and began his UNC Charlotte career in January of 1970. “I planned to stay a year and a half,” he said, “and then move on. But I liked Charlotte, and I saw an opportunity few faculty members will ever have … to play a major role in the development of a ‘new’ college of engineering.” Bayer retired from UNC Charlotte in 2006, a career of 36 years.

With Bayer and Evett as the only faculty members, civil engineering graduated its first student, Lewis Thorne, in 1970. Thorne was followed in 1971 by John Clemmer, James Dunn, Danny Ewing and Richard Morton. Some of other first civil engineering students at the time included Byron Bailey, David Grey, Johnny Graham, Bill Crowder and Ricky Deese.

“While Dr. Evett was our first faculty member and led the department during its first few years,” Bayer said. “Carlos Bell was the first official chairman of the Department of Civil Engineering from 1972 to 1975.”

Bell was followed as chair by Richard Phelps from 1975 to 76, Ellis King from 1977 to 1994, David Young from 1994 to 2012, and then John Daniels who became chair in 2012 and was still serving in that position when this was written in 2015.

In 1975, the American Society of Civil Engineers approved the UNC Charlotte student chapter as a national ASCE member. Student Johnny Graham was the first president and Bayer was the faculty mentor.

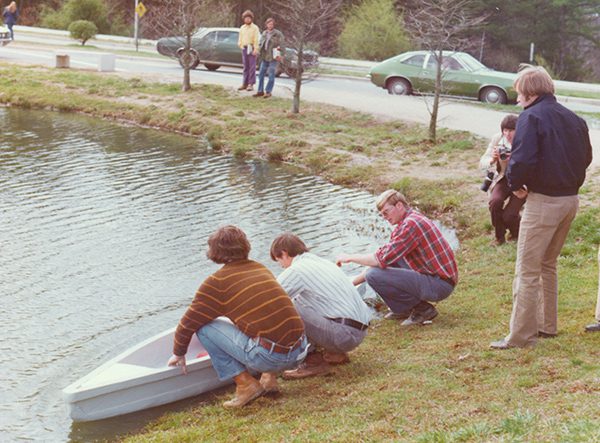

“Our first concrete ‘boat’ was the brainstorm of Johnny Graham and Byron Bailey in the summer of 1974,” Bayer said. “Both had read about a concrete boat race ‘up north’ in ASCE Magazine. Graham, Bill Crowder, David Grey and Ricky Deese were the primary students involved in the design, along with Byron Bailey, Mike Clark and Barry Christopher. The first Southeastern Regional Concrete Boat Race was hosted by N.C. State and held at a lake in McGregor Downs near Raleigh. We won first overall in that competition. Thus the concrete canoe became our chapter’s first “tradition.” Our chapter went to the National ASCE Concrete Canoe Race finals for the first time 1990.”

Before he became one of UNC Charlotte’s first civil engineering students, Johnny Graham had served in Vietnam in 1968 and 1969. He had been seriously wounded and spent six month in the hospital. When he returned to the states in 1970, he got married and became interested in computers and engineering.

“I thought I would like to be an engineer, but I didn’t know what kind of engineer,” Graham said. “I came up here to see what was going on, met Dave Bayer, and he convinced me to major in civil engineering.”

The civil program was officially known as Urban and Environmental Engineering at the time, and had about 20 students enrolled. “We didn’t have multiple lab sections,” Graham said, “because we all fit in one. Everything was in the Smith Building, even the computer. We wrote software programs and put them onto punch cards. You would turn in your cards and then come back the next day to get your run results and your deck of cards back.”

Many of Graham’s classmates were also Vietnam vets and they all studied together and helped each other out. They also played together and got into some of the same trouble together.

“We used to play pig pong a lot at the student union,” Graham said. “We called Bill Crowder Spider Man because of the way he spread out. When we built the concrete canoe, we did it in one of little labs on the back side of the building. We had finished working on it one night, and I was supposed to be the boss, so I sent someone to get beer and someone to get a ping pong table. He said “Where do I get one?” and I said “I don’t care.” He got the table. I don’t know where it came from. I’m sure there was a receipt. There was a rumor it came from Architecture. When we finished the canoe project we put the table in the structures lab. Bayer said he wanted it gone when we graduate. So I took it. I think we had our first class reunion the day after graduation. I had the ping pong table in my basement for years for all of our other reunions, until one time it disappeared again. I don’t know where it went.”

The group was very proud of its first concrete canoe and winning the ASCE competition. “The first ASCE was a big deal and winning was a big deal,” Graham said. “It was a good canoe, but unfortunately the professors did a race in it and they wrecked it. We had to put back together with duct tape.”

After Graham graduated in 1975 he went to work for an environmental company and then ran a construction company. He started working on his master’s degree in 1980 and then went on to the inter-institutional doctoral program between UNC Charlotte and N.C. State, graduating in 1984. At that point he began teaching as a civil engineering faculty member at UNC Charlotte.

As a teacher, Graham said he emulated the style of Bayer, to a degree. “Bayer was colorful and interesting, dressed colorful, used colored chalk on the chalkboard and all that sort of thing. I moved around a lot and used my hands. I didn’t even use my cane when I taught. Adrenaline just kind of took over. For me, the classroom was the best place I could go.”

As a faculty member, Graham stayed active in ASCE. He was an important part of the ASCE annual Chili Cook Off tradition, which started in 1989. For the cook off, faculty members made pots of chili to be judged by the student members who ‘paid’ with donations of canned goods to be presented to the Metrolina Food Bank or other similar organization.

“I won the cook off about 14 times in 25 years,” Graham said. “I won’t give you my receipt, but if you drop by the house I’ll feed you some.”

The growth in UNC Charlotte during his time as a student and professor was unbelievable, Graham said. “It was fun growing up with the university and fun growing up with Charlotte,” he said. “I did a lot of my transportation research out on all the roads of Charlotte. I always thought of this area as my laboratory. It has really grown and it has been great to be a part of.”

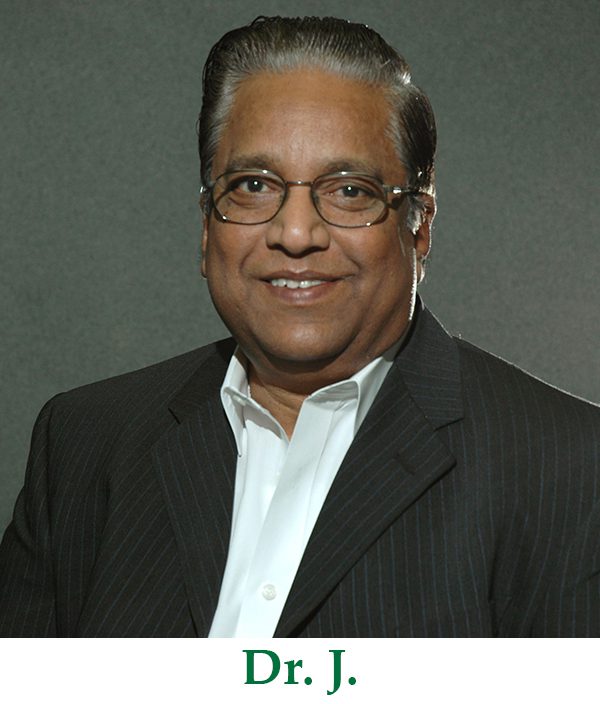

Another faculty member famous for his colorful blackboards was Rajaram Janardhanam, better known as “Dr. J.”

“Dave Byer gave me the name ‘Dr. J.,’” Janardhanam said. “It was back in the time when Julius Irving was playing basketball for the Philadelphia 76ers and was known best as ‘Dr. J.’ He was known for his colorful, creative playing style. I was known for my colorful blackboards. And ‘Dr. J.’ was also a lot easier for students to pronounce.”

Janardhanam came to UNC Charlotte in 1980. There were five civil engineering faculty when he started. His research areas were geotechnical engineering and engineering education.

“There was no research flavor in the university when I started,” Janardhanam said. “I was hired to teach, but had come from Virginia Tech where there was a strong research culture. I got the first UNC Charlotte NSF research grant in 1984 to study liquefaction of soil. I also got the first grant in six figures.”

Janardhanam had numerous successes in research and was also extremely busy in faculty governance and university administration. His first love, though, was always teaching.

“The students were my life,” he said. “Working with my students and teaching the classes, that’s was my bread and butter. In the early days I knew each and every student by name. Even now I have a good relationships with many former students.”

When he was interviewed in 2014, Janardhanam said he didn’t plan to retire until the age of 80. He planned to endow a scholarship before retiring, a goal he had been saving money for for years. “I was almost there when the market crashed a few years back,” he said. “Now, I’m having to work longer to get the endowment back to where it needs to be.”

A goal throughout Janardhanam’s career was to be a good influence on his students’ careers and lives. “When you go back and ask students 20 years after they have graduated, ‘Who was a faculty member who impacted your life?’, I want them to say my name. That is how I really lived and served. And it is happening. That’s why my life is so blessed.”

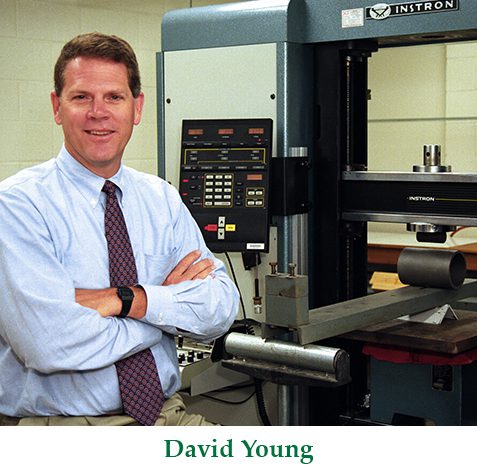

Another civil engineering faculty member rewarded with a fulfilling career at UNC Charlotte was David Young. Young came to the university in 1985.

“I saw an ad for UNC Charlotte that said it was in process of building graduate programs,” Young said. “I thought that sounded interesting. I applied, was hired and never look back. It has been a great ride.”

Before coming to UNC Charlotte, Young worked as a project manager, building designer and construction manager while simultaneously completing his master’s at Clemson and Ph.D. at Virginia Tech. At UNC Charlotte he served as a civil engineering faculty member from 1985 to 1992, associate chair of civil engineering from 1992 to 1993, acting chair 1993 to 1994 while Ellis King was on sabbatical, and then full chair from 1995 until 2012.

“Ellis King had been chair for 18 or 19 years,” Young said, “and then I took over. So, we had only two chairs for almost 40 years.”

Civil engineering had a number of senior faculty members in the department when Young became chair. “I learned early on wasn’t going to boss them around,” he said. “My approach was much more to encourage, motivate and facilitate. I wasn’t going to try to force them to do anything. Maybe that’s why I lasted so long as chair, because the faculty liked that. My philosophy as chair was to do whatever I could to help the faculty succeed. I enjoyed working with people, laying out plans and then making the plans happen. Overall it was a very good experience.”

There were several curriculum revisions during Young’s tenure as chair, but the commitment to applied, hands-on learning was always the foundation of the program. “Our program had a large number of laboratories,” Young said. “That was the case when I got here and it didn’t changed much at all. The purpose was when students actually saw the real thing in the lab, it made them a better designer. It was the cornerstone of the college. A lot of employers over the years really liked that aspect of our program. I heard many comments about how well prepared our students were and how they hit the ground running.”

The student population of civil engineering became more traditional in the 2000s, with more full-time students who came straight out of high school and who lived on campus. “I think that was a good thing,” Young said. “We used to have a requirement that faculty had to teach night classes. For 27 years I taught on Wednesday nights, that was my night. Now we don’t have nearly as many after-hours classes.”

Another aspect of civil engineering that changed greatly during the 2000s was the growth of the graduate and research programs. The growth was made possible by the addition of new faculty members who were more research oriented, including Jim Bowen, Helene Hilger, David Weggel, Janos Gergely, Marty Kane, John Daniels and Vincent Ogunro.

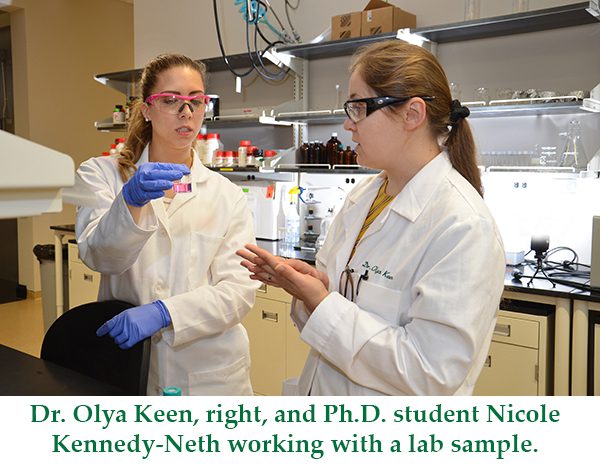

In 2004, the Infrastructure, Environment and Sustainability (INES) doctoral program started at UNC Charlotte, with civil engineering as one of the main participants and Young as a co-directory. A multidisciplinary program, INES engaged seven departments including civil engineering, geography and earth science, biology, business, chemistry, systems engineering and architecture.

“The INES had some unique features,” Young said. “It provided opportunities to work with faculty from other departments, and I really enjoyed that. We got it up and running and it did very well.”

At the same time that INES was getting its start, the Civil Engineering Department was moving from the Smith Building to the Cameron Center, and the IDEAS research center was starting. At that point Young stepped down as co-director of INES.

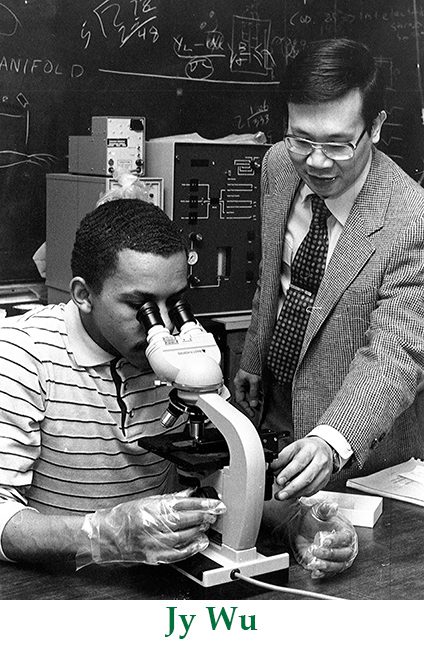

“Jy Wu had been the graduate director in civil engineering for 15 years, and he said he’d like to do it (lead INES),” Young said. “He came in and did a great job.”

Civil engineering research continued to increase in the 2000s and 2010s with the addition of new research centers including the Infrastructure, Design, Environment and Sustainability (IDEAS) center, the Energy Production and Infrastructure Center (EPIC) and the Center of Transportation Policy Study.

“It was a natural evolution with the research centers and the Ph.D. program linking together,” Young said. “The Ph.D. students stayed longer and worked at more advanced levels, which allowed more complex research project. And the faculty from multiple colleges and departments were able to coalesce around larger themes.”

In 2012, Young stepped down as chair of civil engineering to become associate director of EPIC. “I had been at it 18 years and it was a good time for a change,” he said. “I was intrigued by EPIC. I knew nothing about energy and at 60 years old I had to reinvent myself. At times working at EPIC was overwhelming, but it was invigorating.”

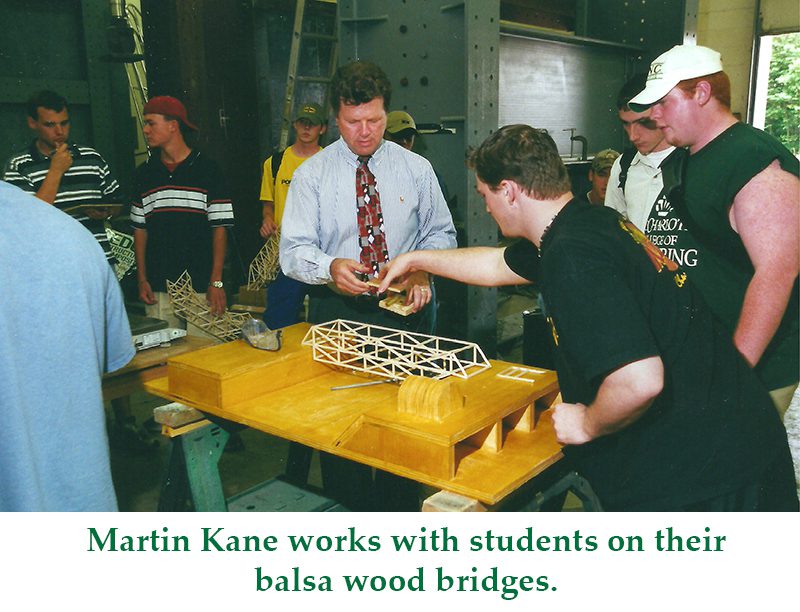

For his first 20 years in the UNC Charlotte Civil Engineering Department, faculty member Martin Kane said it was the people who made the department a special place to work. “I liked the people I worked with,” Kane said. “These were a great people. We had our differences, but we could disagree without being disagreeable. Our philosophy was to hire good people, people you would like to work with, and people you thought the students would like in the classroom.”

Kane was in the Navy for six years after high school and then went into the workforce for eight years before deciding to get a college education. When he was finishing his bachelor’s degree at Michigan State at the age of 35, he decided that to be competitive with his younger classmates in the job market he needed a master’s degree. He stayed for his master’s degree and then the professor he worked for won a grant that he wanted Kane to work on with him, and convinced Kane to continue on for a Ph.D. So in 1995, Kane graduated with his Ph.D. and came to work at UNC Charlotte.

Kane became undergraduate coordinator for civil engineering in 2005. “Thankfully Dave Bayer’s office was two doors down from mine,” Kane said. “I think I probably wore out the floor between Dave’s office and mine, asking what can and can’t be done. He and Jack Evett were both great. They were always looking to do whatever they could to make things better for the students. Their goal was to make the students successful when they went out into the big wide world. If it was for the students, they would do whatever they could.”

Kane was faculty mentor for the ASCE chapter for many years, and was always impressed at the hard work the students put in to projects they got no academic credit for. “They had built a legacy that made others want to participate and do well,” he said. “And they were competitive in wanting to beat the other schools. They had some good successes.”

Working on teams and on projects was a constant part of the civil engineering students’ education. “I told students ‘If don’t want to get dirty you don’t want to be in civil engineering. You’re going to get dirty and everyone is going to do it.’,” Kane said. “Employers appreciated this philosophy and when I asked them if our students they hired were performing well, usually one of their first comments was that the students came in ready to work, which was a direct result of the hands-on education they got here.”

John Daniels came to the Civil Engineering Department in January of 2001, immediately after completing his Ph.D. from the University of Massachusetts-Lowell.

“I came in at the time when I had a chance to interact with the founding members of the department,” Daniels said. “That gave me a good sense of the culture and history of the department, why they did what they did, and their focus on education.”

The culture he found was one of dedicated faculty who provided accessibility to students on all levels. At many universities the drive for increased research was opening a gap between the students and their professors.

“Here we hired people who had the same passion for students and teaching as they did for research,” Daniels said. “They could teach at all levels and were skilled at imparting their knowledge.”

The culture of teaching, research and community service was consistent for whole history of the Civil Engineering Department, Daniels said. “Research always did occur in the department, and the role of the undergrad in it was always strong. A lot of that was from necessity, because we didn’t always have the grad programs. The role of our undergrads in research was unique before it was fashionable. Now it is being pushed by NSF and others.”

Daniels’ personal research focus was on barriers for industrial waste and included projects such as adding polymers to clay liners to improve their efficiency. He expanded this work into the area of coal fly ash research, a field shared by a number of his fellow civil engineering faculty members.

“In 2015 our department had more faculty with coal ash expertise than any other department in country,” Daniels said. These researchers included Miguel Pando, Milind Khire, Vincent Ogunro, Rajaram Janardhanam, Shen-En Chen and Brett Tempest.

From 2007 to 2010, Daniels did a three-year rotation at the National Science Foundation in Washington D.C. In his first two years he worked in two divisions for NSF, one managing engineering research centers and one on cross-disciplinary programs. In his third year he managed budgets for geotechnical and geo-environmental engineering research.

“It was a natural fit for me,” Daniels said. “It gave me the opportunity to see what works in engineering research centers, which allowed me to provide feedback and input to other faculty who were trying to get funding from NSF.”

Daniels returned full time to UNC Charlotte in 2010, again teaching undergraduate and graduate classes. He became more involved with the IDEAS center and with the new Center for Sustainably Integrated Buildings and Sites (SIBS).

Another research center that was gaining more and more momentum in 2012 was EPIC. The program moved into the new EPIC building, along with the Civil and Environmental Engineering Department and the Electrical and Computer Engineering Department. David Young decided to step down as chair of civil engineering to go to work for EPIC.

“David Young decided he wanted to step down to be a part of EPIC,” Daniels said. “The opportunity came to me to be interim chair. At that point I had to make a decision about whether I wanted to build my own research programs or grown the overall programs of the department. I made the conscious decision to pursue administration and became chair of civil engineering.”

Daniels credits his colleagues in civil engineering with much of his success as a teacher, researcher and administrator. “Helene Hilger was very helpful across a whole array of issues, from strategies for prepping for courses, to working with graduate and undergraduate students, to applying for research grants,” he said. “She was very helpful, very candid and very forthright.”

Daniels credits David Young with teaching him a lot about leadership. “Specifically, I learned a lot from his positive disposition on virtually every issue,” Daniels said. “Whatever the challenge or issue, Young was always positive and willing to look beyond the two points of view to third option, a thing you may not have thought of.”

Going forward, Daniels said he see even more opportunities for the Civil and Environmental Engineering Department to contribute to research that impacts the national and international level. “I also see us doing more things that are innovative in teaching,” he said. “In 2014, we won the Provost’s Award for Excellence in Teaching, which is an indication that we are poised to do more great things in teaching, as well as in research.”