Founding 1965-1977

In the spring of 1965, Charlotte College’s first bachelor’s degree engineering graduates took their place in the world of professional engineering. In the summer of 1965, Charlotte College officially became the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, an institution of the State of North Carolina’s university system. The elements were now in place, and upper-level engineering and technology programs at the new UNC Charlotte began the foundational chapter in their history.

The engineering faculty of the period say it was one of those great times. A time when things were new. Nothing was done the way it had always been done, because it had never been done. Everything had to be learned from scratch and progress was slow. Growing pains were real. It was hard, but it was exciting. Everyone knew where it could lead. Everyone knew it could be great.

Getting Started

The engineering program was known as the Department of Engineering in 1965. It was led by Dr. Newton Barnette, who had come to the program as a distinguished professor and chairman of engineering in 1964. Fellow electrical engineers Burt Wayne and Bill Smith also arrived as full-time faculty members in 1964. They were followed in 1965 by mechanical engineers Walt Norem and Rhyn Kim.

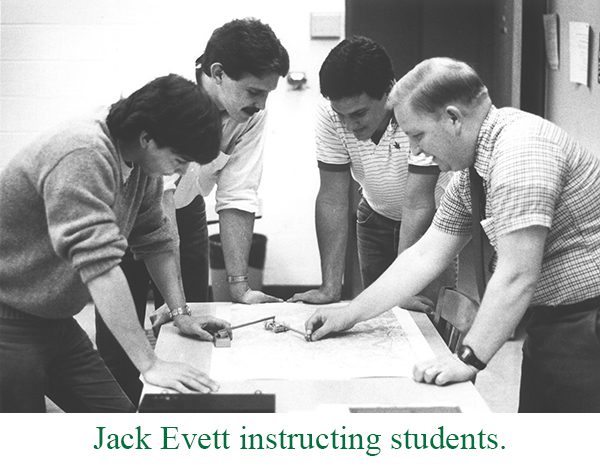

Civil engineering faculty member Jack Evett came to the program in 1967. “Essentially it was just electrical and mechanical when I arrived,” Evett said. “Newton Barnette, Burt Wayne and Bill Smith were the electrical faculty. Walt Norem and Rhyn Kim were the mechanical faculty and that was it. I was number six. I was the first civil. There was nothing when I got here that would let you think there was any type of civil engineering program.”

There were about 100 engineering students at the time, out of the 2,000 students enrolled at UNC Charlotte. There were no civil engineering students.

The university hired Carter Grant in early 1969 to start the engineering technology program. Grant was an electrical engineer, and he began teaching the first ET courses in electrical engineering technology in fall 1969. Civil and mechanical engineering technology courses started in 1970. Cheng Liu was the first faculty member in Civil ET and Ron Priebe was the first faculty member in Mechanical ET. George Elliott came on as a second hire in electrical ET.

“We had nothing when I arrived,” Priebe said. “Not a text book, not a note, not a laboratory experiment, and I actually came before classes started, so not even a student. What we did have was something new, something rather exciting. It was a different opportunity and a different atmosphere. I think it was really very hard work. We taught everything in the program that was taught.”

The ET program officially had 12 students in 1970, divided between civil, mechanical and electrical engineering technologies. The ET students had to come in through state community colleges with their associate degrees completed. They came to UNC Charlotte to complete their final two years in what was a very economical, attractive, two-plus-two program that culminated in a bachelor’s in engineering technology.

Along with ET, the engineering programs were also hiring new faculty in the late 60s and 70s. One of these was civil engineering professor David Bayer, who arrived in January 1970 and would go on to be better known as “Doc B.” for the remainder of his long UNC Charlotte career.

“Everything was in the Smith Building when I arrived,” Bayer said, “and parts of it were still pretty bare. They asked me if I’d mind teaching a concrete lab and I said, ‘No problem, where is it?’ They said ‘We don’t have one.’ So, we had to go build it.”

The Students

Many of the first students during those years were military veterans. A number of them had wives, children and full- or part-time jobs.

“Engineering was a big mixed bag of students,” Bayer said. “We had a lot of Vietnam vets and they were older. That’s how I got my nickname ‘Doc B.’ I didn’t want them to call me ‘Doctor Bayer’ because they were the same age as me. I didn’t want them to call me ‘David’ either, so we settled on ‘Doc B.’ and it stuck.”

Aside from assigning nicknames to their professors, the students were serious and hard working. “I thought they were the best students I ever had,” Bayer said. “They were absolutely motivated. They did not want to miss a class. The reason they were so dedicated, I think, is they felt cheated out of a certain portion of their life having been to Vietnam. They wanted to catch back up as best they could and they didn’t want any delay. They wanted to graduate and get back into life.”

Jack Evett concurred with the description of the initial students. “Many of that generation were the first ones in their families to get to go to a college or university and it meant something special to them,” he said. “It wasn’t something you took for granted that when you finished high school the next step was automatically college. The students and their families were making sacrifices so they could be there, and they took their studies seriously. There was actually a lot of pressure on some of them.”

Organizing

The UNC Charlotte engineering program in 1965 was officially the Department of Engineering. It carried the same designation as other university programs such as the Department of Chemistry, Department of History or Department of English. With the growth of multiple disciplines within engineering and engineering technology, though, the program was more complex than a single department. So in 1970, the university designated engineering as a division, which was made up of departments.

Norm Schul was the department chair of Geography and Geology at that time, and was one of the developers, along with Newton Barnette and other university leaders from the humanities and the sciences, in the formation of the multiple divisions plan.

“The concept of academic divisions took place on my living room floor,” Schul said. “We met at my house, got down on the floor with all our papers, my wife Mary Ann served us Cokes (we decided not to have any hard liquor until we got our work done), and we started organizing the university into divisions. We turned in a report to the chancellor, who sat on it for a while, but eventually said ‘This is a good way to go.’”

The plan extended beyond just organizing what already existed and made recommendations that professional programs such as engineering, business, education and nursing needed to be the strengths of the new university, because these were the programs the community of Charlotte needed.

“We looked at other urban universities to see what they had, and we tried to learn from them,” Schul said. “As an urban university knew we needed to include engineering. There was some conflict with this on campus. Some people wanted us to be a pure liberal arts school. They even argued that we weren’t an ‘urban university’, since our campus at the time was pretty much out in the country. They joked that we were UNC Newell. But we didn’t want to become a service station that offered every little program in the world. We wanted to stay focused on programs with an academic research perspective.”

The designation of academic units as “divisions” lasted from only 1970 to 1973. The university and its programs continued to grow so fast that the “divisions” were reorganized as “colleges” in 1973. The name “College of Engineering” was then used for the first time at UNC Charlotte. The departments that comprised the new college were:

- Engineering Analysis and Design

- Engineering Science, Mechanics and Materials

- Urban and Environmental Engineering

- Engineering Technology: comprised of Civil ET, Electrical ET and Mechanical ET

“At that point in ’73 we became the ‘college,’” Evett said, “with a dean, four departments and four department chairs.” The department chairs at the time were Burt Wayne in EAD, Walt Norem in ESMM, Carlos Bell in UEE, and Carter Grant in ET. Newton Barnette was the overall dean.

Smith Building

One of the first buildings on the new UNC Charlotte campus and the first home of engineering was the Smith Building. When it was completed in 1966, it was actually known as the Engineering Building, even though it contained a number of other programs in addition to engineering.

The 71,000 square-foot, $1.6-million facility was the largest classroom and laboratory building on the campus at the time. When finished, it housed engineering, mathematics, geography and geology, a physics lab, a psychology office and the university computer center.

“We were all crammed together in the Smith Building,” Farid Tranjan of electrical engineering said. “The building always leaked. I remember calling facilities to tell them one of the leaks was getting so bad it was overflowing the trash can we had put under it. They said to get a bigger trash can.”

As chairman of Geography and Geology, Norm Shul had his office in the Smith Building in 1967. “Actually it was a conference room on the third floor that I was using as an office,” Shul said. “The chair of psychology had an office nearby. The next year the coach of the basketball team, Bill Foster, moved in also. So NCAA basketball at UNC Charlotte actually got started in the Smith Building.”

One of Evett’s early memories of the Smith Building was that faculty had no phones in their offices. “There was a phone in the department office and we had a buzzer in our office,” he said. “If someone needed to call you they called the department phone, and the department secretary buzzed you and you went down to take your call. So, I had to hold all my phone conversations in my department chair’s office.”

Parking was much easier and more convenient in those days, with a gravel parking lot right next to the building. The big windows in the buildings could be opened and closed, and people really wanting to take a short cut could step out of their windows directly into the parking lot.

Sheldon Smith

On December 15, 1968, UNC Charlotte dedicated the Engineering Building in honor of Sheldon P. Smith, in a ceremony held in the Cone University Center. The Smith family presented a portrait of the building’s namesake to be placed in the facility.

Smith had worked for Douglas Aircraft and was instrumental in starting the engineering program in Charlotte to support his company’s need for engineering education. As an advocate for the college, Smith once said, “If we marry the manpower development of this Charlotte College area of some 1 million people to the tremendous demand of technical industries for engineers and scientists, we will accomplish two ends: to help satisfy the great national requirements for engineers and scientists and to improve the usefulness and economic standards of the residents of North Carolina.”

Born in Redlands, Calif., on March 26, 1910, Smith graduated from Pomona College in 1932 with a bachelor’s degree in physics. During World War II, he served as a lieutenant with the Engineering Division of the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics and was assigned to the missiles branch. Following the war, he was a missile project engineer with the Douglas Aircraft Co. Prior to moving to Charlotte, he was an assistant design engineer for missiles at the company’s Santa Monica facility. Smith left Charlotte to become vice president of Douglas Aircraft and vice president of Douglas United Nuclear Corp. in Hanford, Wash. He died April 28, 1966.

Accreditation

The first major challenge the new College of Engineering faced was the accreditation of its programs by what was then the Engineers’ Council for Professional Development (ECPD).

“Newton Barnette got us through our first accreditation,” Evett said, “which was quite an achievement. The first accreditation is a lot harder than a reaccreditation. That was 1973, and we went in with six programs on the line and came out with all six programs accredited for the full six years.”

Getting those first accreditations was never a sure thing. The programs were young, the facilities were sparse and the faculty was small.

“It was actually a miracle,” Evett said, “particularly civil, or what was UEE at the time. We only had two faculty members.”

A lot of the credit for UEE’s success was due to the personal charm and charism of chair Carlos Bell. “Carlos was a true intellectual and could talk on any subject,” Evett said. “His accreditor was a guy from California, and Carlos hit it off with him talking about wines and vineyards and such. That saved the day. It really did.”

Graduate Programs Start

With undergraduate programs established and accredited, the next step in the college’s growth of academic programs was the creation of graduate programs. The first logical step was to start a master’s degree program. Since all of the engineering disciplines wanted a master’s, it was decided that the college’s first graduate degree would be a generic Master of Science in Engineering.

“The master’s program started about 1975 or 1976,” Evett said. “It was a Master of Science in Engineering, so all departments could participate in it.”

While planning the degree, there was tension between faculty members who wanted a thesis requirement and those who didn’t. Those on the thesis side wanted it because it would provide them with students to help with research. Others argued that most of the students would be older, would already have a lot of professional experience, and just wanted to do their coursework, be done and get their degree.

“So we offered both options,” Evett said.

A number of the first master’s students came from Duke Power. Duke paid their tuition, and they worked on their degrees as part-time students and full-time Duke employees.

The college had also started its co-operative education program at the same time, and many of the first positions were at Duke Power. It was the start of a long relationship between the College of Engineering and Duke Power.

Walt Norem

One of the key leaders during the early history of the College of Engineering was Walter Norem. He was one of the first mechanical engineering faculty members hired and was the chair of the ESMM Department (later Mechanical Engineering). He was also instrumental in the early administration and organization of the college, including the accreditation of ESMM.

“He was possibly the most important person in that era,” Evett said. “He was one of my very best friends. I actually lived in his attic the second year I was here. He had a kind of unfinished attic and I lived in it for a while. Walt was a hard worker; I mean he did everything. He was just a busybody and I mean that in the best sort of way. He had his hands in everything. And he could handle everything. It was pretty well felt by everybody that he was the dean in waiting, so to speak.”

Ron Priebe agreed that Norem was an incredibly hard worker. “Walt Norem was a metallurgist,” Priebe said. “He was very active with outside consulting as a practicing metallurgist. If you needed him and he wasn’t in his office, you could probably find him in his lab with a rubber apron on running some tests.”

As part of his consulting work, Norem was in Charleston, South Carolina, the week of September 9th, 1974. He was returning to Charlotte in the early morning of September 11th on Eastern Air Lines Flight 212.

“He was flying back to get back to teach his classes,” Evett said, “He was flying in at 7 am or something like that. I’m sure he would have come straight to campus to teach his classes, because that’s just the way he was. But that plane didn’t make it.”

Flight 212 crashed in dense fog short of the runway at Douglas Municipal Airport. Seventy-two of the 85 people on board were killed immediately, including Walt Norem.

“I can vividly remember that day,” Schul said. “Walt was a neighbor of mine. I knew him well and thought a lot of him. He was very serious, but a real nice guy. His cousin was a friend of mine and a member of my Rotary Club; he’s a dentist here in Charlotte. I had just gotten into my office and got a phone call from his cousin and he said ‘I think Walt was on the plane that was coming in from Charleston and is probably killed.’ I called home to my wife and told her to go be with Linda (Walt Norem’s wife). It was a terrible day.”

The tragedy weighed heavily on everyone who knew Norem, Evett said. “It was devastating. To all of us. One person in particular was Newton Barnette. Newton had a kind of father-and-son relationship with Walt, and was essentially grooming him to be dean. After the crash, Newton just about disappeared for almost a month.”

Newton Barnette

Born in Arkansas in 1917, Newton Barnette earned a bachelor’s in 1944 from Louisiana Technical University, a master’s in 1946 from Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, and a Ph.D. in 1958 from Cornell University, all in electrical engineering. He was known by his peers as an intellectual who had a number of non-intellectual hobbies including woodcarving, photography and show dogs.

UNC Charlotte founder Bonnie Cone recruited Barnette from Georgia Tech in 1964, tasking him with building the engineering program. His career at UNC Charlotte included serving as dean until 1976 and being named a distinguished professor of engineering in 1977. He retired from the university in 1983.

“Newton was kind of a laid-back sort of individual,” Evett said. “He did at times ride a motorcycle, which was kind of out of character with the rest of his persona. He deserves a lot of credit for building the engineering program.”

Schul remembers Barnette from their interactions as early leaders of university academic units. “Newton was a very inward oriented type of person,” Schul said, “and he was very suspicious of anything outside engineering. He felt threatened by some programs and some individuals. We, the other deans, collaborated very well, Newton didn’t. I think part of what had a negative impact with him was he was building the engineering college around Douglas Aircraft and then they moved to California. He let that gnaw on him.”

As a fellow electrical engineer who came to UNC Charlotte in 1976, Dr. Yogi Kakad knew Barnette as a peer and a mentor. “I got to know Newton Barnette very well,” Kakad said. “He was a very interesting man; an intellectual; maybe not a good administrator, because he was always nervous about making decisions.”

Kakad had come to UNC Charlotte from the University of Florida, where he had been teaching as a post-doc. “Barnette was teaching a class here that I had been teaching in Florida and had a problem he couldn’t solve,” Kakad said, “I sat down and solved it for him and that impressed him. We became very good friends, because we taught in the same department and taught the same courses. He always pushed me to achieve my maximum. He said ‘Son, I know you are teaching four courses but don’t drop your research, continue with it.’ He always treated me like his own son.”

When Barnette retired in 1983, he passed his entire collection of electrical engineering books on to Kakad. “He said I was the only one he wanted to have his books,” Kakad said. “He was very good to me.”

Barnette stepped down as dean in December 1976, having during his tenure established the undergraduate academic departments, earned the first undergraduate degree accreditations and started the master’s program. In addition, by the time he retired from the college seven years later, he had taught almost all of the first generation of electrical engineering students at UNC Charlotte.

The next chapters in the college’s history were led by Bob Snyder, who in his 22 years as dean raised UNC Charlotte engineering to new levels in programs, research and facilities. All of this while reinforcing the college’s dedication to students, and always finding time for his favorite part of the day – the time when he was in front of students teaching.